Controversy over the recent sale of Welsh semiconductor foundry Newport Wafer Fab (NWF) to one of its customers — Dutch chipmaker Nexperia, owned by Chinese technology group Wingtech — has raised questions about how best to protect and develop the UK's semiconductor industry, with some onlookers warning that any legislative tools may fall short without an overarching plan for moving the sector forward.

The sale was completed in July but was swiftly followed by protests from senior political figures who questioned the advisability of selling a UK semiconductor asset to a Chinese-controlled entity. Prime minister Boris Johnson on 7 July instructed the UK's national security adviser, Stephen Lovegrove, to review the transaction, with a report due to be released in the near future. Meanwhile, UK businessman Ron Black has put together a consortium to offer a rival bid should the government intervene. Legislation designed to protect critical infrastructure and technology from external threats — the National Security and Investment Bill — will come into force on 4 January 2022, effectively providing a legal route to invoke a retrospective mandate to freeze the sale.

NWF was built in 1982 by one of the world's first semiconductor companies, Inmos. Inmos was founded in 1978 by an English and a US engineer with a £50mn ($70mn) grant from the UK government through the National Enterprise Board. Inmos produced the world's most advanced memory chips and captured over half of the global market. But it fell victim to a boom and bust in the memory market, a cyclical trend that persists today. And the parallel processing architecture that Inmos envisioned, the transputer, failed to become the dominant technology.

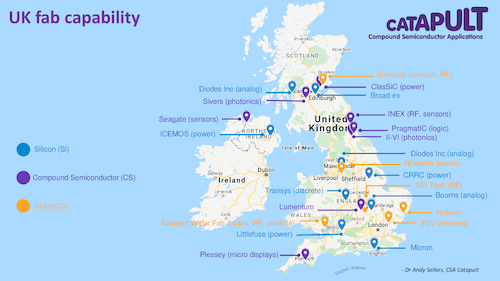

Almost four decades and a string of corporate owners later it became what is known as an open access foundry. Open access foundries sell manufacturing capacity to other companies that choose to produce their chips there. Prior to the acquisition, Nexperia was one of its customers and its main product line was a type of advanced power transistor called a MOSFET, used for switching in power applications. It is a high-volume product with global demand of around 100bn devices a year. NWF is one of the UK's largest chipmakers along with Nexperia in Manchester and Gfab in Greenock Scotland (see map). Gfab is owned by US semiconductor manufacturer Diodes, which bought it from Texas Instruments in April 2019.

The UK has around 23 fabrication plants, some capable of producing over 1bn chips/yr. The silicon plants are mostly on older platforms. But there is also a high concentration of capacity to produce a type of next-generation chip called a compound semiconductor. These combine different elements to make highly engineered chips for specific applications. NWF was also entering this market by offering foundry services to compound semiconductor companies and had won several contracts from the UK government-funded Innovate UK.

A recent report from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy highlighted the critical nature of the industry and the need for a strategy to secure resilience and build upon the UK's semiconductor capabilities.

Chipmakers' planning problem

The investment timeline for going from an empty lot to a profitable chip manufacturing facility can be as long as 10 years. This, combined with high capital and operating costs, has created an active secondary market, and plants around the world can go through many corporate owners. The risk for an older plant is that if it is not upgraded to newer platforms, it is destined to become a silicon workhorse operated flat out until its production process becomes obsolete.

But there are even more serious implications. Automakers around the world are all too painfully aware of the consequences of sudden events creating a mismatch between demand and supply. The Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in volatile swings in demand for automotive chips, causing reverberations and repercussions in the supply chain that continue to wreak economic damage across the industry.

A strategic solution

The level of trust and understanding between governments and the semiconductor industry is light years ahead of where it was in the early days of computers. In the 1980s, when a senior economic adviser to the White House quipped "computer chips or potato chips there is no economic difference", the president of a large US chipmaker sent him a violin with a note attached that read "fiddle on this while Silicon Valley burns".

But what has changed in the meantime is the complexity of the industry. The most complex manufacturing process on earth produces a product that is so small and so light it can be sent in the post. This unusual quirk, combined with some extraordinary economic pressures and relentless technological advancement, means that where once a chip company designed, manufactured and sold chips, that is now the rare exception. Different stages of the process have evolved into separate industries. The semiconductor sector has the largest global footprint of any industry, which makes it uniquely vulnerable to global political tensions. And industry experts warn that without an over-arching plan, the ability of the UK to protect its semiconductor industry, regardless of the legislation at its disposal, will be limited.

By Caroline Messecar